INTERVIEW: Fan Fiction at Swarthmore

Once considered the domain of only the most secretive of nerds, their taped-up glasses sliding down their noses as they stare into glowing green computer screens, fan fiction has recently been drawn ever further into the mainstream. It has even been written about in TIME and WIRED magazines.

With fan fiction, writers can do anything within the worlds others have created: Argus Filch can romance Augusta Longbottom; Sansa Stark can double as the Doctor; Marty Stu can join the Ninja Academy and fight alongside Naruto and Sasuke; and even a mere look between Sherlock and John can hold immense amounts of pain and longing.

One of the most popular works of fan fiction of all time, My Immortal, a Harry Potter fan fiction, holds the unofficial title of "Worst Fan Fiction Ever." However, as Sturgeon's law reminds us: ninety percent of everything is crap, but the remaining ten percent is worth dying for.

The best fan fiction authors can devote hours, months, or years of time crafting intricate, well-written stories. Authors can also garner huge online followings for their work by posting them on sites such as Fanfiction.net, An Archive of Our Own, or LiveJournal. However, there are not many people who will admit to writing fan fiction in real life.

For Josh Ginzberg '15, who writes fan fiction for Avatar: the Last Airbender and the video game Mass Effect, among others, his foray into the world of fan fiction began in school. As part of a grade school assignment, he had to write his own fairy-tale, and he wrote a crossover between Cinderella and Star Wars that, sadly, "is never seeing the light of day."

His love of Avatar came about after an intense marathoning session of the show. He began writing missing scenes and "dramatizations" and novelizations of episodes of the show, with the occasional "shipping" (romantic or sexual fiction) thrown in, adding his own twists into the show's mythology.

After taking the course "Fan Culture" with Professor Bob Rehak, he developed his current view on "shipping" in fan fiction.

"I don't really care what you ship. I'll ship everything. It's a nice challenge to be able to see if I can put these two characters together, even though the show wouldn't necessarily support it. But it's also nice if you support the stuff in the show, because then you can expand on it in a way the show never did," Ginzberg said.

When I asked Ginzberg about whether he thinks an author should be able to exercise control over whether people write fan fiction of their works, he let out a sigh.

"I think they definitely have the right not to want people to play around in their worlds," he said. As a fan fiction writer, he admitted his own bias. "I'm probably more likely on the side of the fanfic writers. As soon as it's out there, and people are reading it, they're already playing around [in their minds]: who cares if they write it out at that point? Do they have the right to think about their fanfic stories? Of course they do."

Ginzberg writes most of his stories during breaks and in transit: on trains, buses, and basically any time he's not at Swarthmore doing schoolwork. He also has several original stories in the works, using his background in political science and Classics to build convincing, complex worlds.

Leah Foster '14, another avid fan fiction writer, recently contributed her fiction to the Homestuck fandom. To write this piece, Foster and a friend wrote through the voices of different characters in a Google Doc. Her Homestuck fan fiction is characterized by romance and what she calls "overwrought angsting." Her writing style has changed from serious and dramatic to more humorous of late, in addition to "general improvement."

Foster gets involved in fandoms often due to fanworks, such as fan fiction and fan art.

"[Homestuck] itself is fairly deep and very funny, and that's the point of it. But you can draw a lot out of that," she said.

When asked about her views on authors who encourage or discourage fan works, Foster replied that authors encouraging their fans to write fan fiction do so as a marketing tactic. However, on the flip side, she feels no qualms writing fan fiction after authors have discouraged the practice.

"It's just like, 'sorry lady. Sucks to suck. You wrote it,'" she said.

While Ginzberg's involvement with fan fiction at Swarthmore has been largely extracurricular, Foster is writing her capstone project for the film and media studies department about fan fiction. Another former participant in the "Fan Culture" class, Foster is focusing on "how slash fan fiction often elides the use of lubrication in anal sex" and how this omission by writers operates within a "heterosexual paradigm, a heterosexist use of queer characters in fiction written by women, for women."

She argues in her project that "fan writers explore femininity and build desirable forms of femininity through slash fanfiction by sticking feminine attributes on male characters and making them androgynous/feminine." She also proposes that "the lack of lubrication [...] and the primacy of anal sex [...] implies the anus as the vagina," which again privileges straight sexual relationships.

While fan fiction is still apparently a rarity even at Swarthmore, Ginzberg and Foster prove that the practice has its Swattie devotees, who treat writing fan fiction with both a sense of fun and of respect. Whether inside or outside the classroom, or in both spheres, these Swarthmore writers apply intellectual inquiry to this wildly popular creative practice.

With fan fiction, writers can do anything within the worlds others have created: Argus Filch can romance Augusta Longbottom; Sansa Stark can double as the Doctor; Marty Stu can join the Ninja Academy and fight alongside Naruto and Sasuke; and even a mere look between Sherlock and John can hold immense amounts of pain and longing.

One of the most popular works of fan fiction of all time, My Immortal, a Harry Potter fan fiction, holds the unofficial title of "Worst Fan Fiction Ever." However, as Sturgeon's law reminds us: ninety percent of everything is crap, but the remaining ten percent is worth dying for.

The best fan fiction authors can devote hours, months, or years of time crafting intricate, well-written stories. Authors can also garner huge online followings for their work by posting them on sites such as Fanfiction.net, An Archive of Our Own, or LiveJournal. However, there are not many people who will admit to writing fan fiction in real life.

|

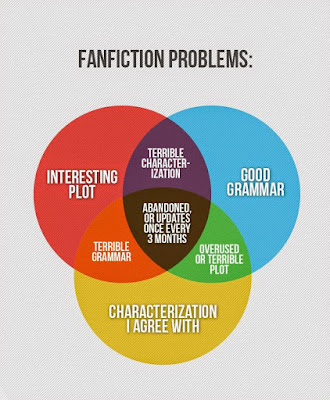

| https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/419186677794828913/ |

His love of Avatar came about after an intense marathoning session of the show. He began writing missing scenes and "dramatizations" and novelizations of episodes of the show, with the occasional "shipping" (romantic or sexual fiction) thrown in, adding his own twists into the show's mythology.

After taking the course "Fan Culture" with Professor Bob Rehak, he developed his current view on "shipping" in fan fiction.

"I don't really care what you ship. I'll ship everything. It's a nice challenge to be able to see if I can put these two characters together, even though the show wouldn't necessarily support it. But it's also nice if you support the stuff in the show, because then you can expand on it in a way the show never did," Ginzberg said.

When I asked Ginzberg about whether he thinks an author should be able to exercise control over whether people write fan fiction of their works, he let out a sigh.

"I think they definitely have the right not to want people to play around in their worlds," he said. As a fan fiction writer, he admitted his own bias. "I'm probably more likely on the side of the fanfic writers. As soon as it's out there, and people are reading it, they're already playing around [in their minds]: who cares if they write it out at that point? Do they have the right to think about their fanfic stories? Of course they do."

Ginzberg writes most of his stories during breaks and in transit: on trains, buses, and basically any time he's not at Swarthmore doing schoolwork. He also has several original stories in the works, using his background in political science and Classics to build convincing, complex worlds.

Leah Foster '14, another avid fan fiction writer, recently contributed her fiction to the Homestuck fandom. To write this piece, Foster and a friend wrote through the voices of different characters in a Google Doc. Her Homestuck fan fiction is characterized by romance and what she calls "overwrought angsting." Her writing style has changed from serious and dramatic to more humorous of late, in addition to "general improvement."

Foster gets involved in fandoms often due to fanworks, such as fan fiction and fan art.

"[Homestuck] itself is fairly deep and very funny, and that's the point of it. But you can draw a lot out of that," she said.

When asked about her views on authors who encourage or discourage fan works, Foster replied that authors encouraging their fans to write fan fiction do so as a marketing tactic. However, on the flip side, she feels no qualms writing fan fiction after authors have discouraged the practice.

"It's just like, 'sorry lady. Sucks to suck. You wrote it,'" she said.

While Ginzberg's involvement with fan fiction at Swarthmore has been largely extracurricular, Foster is writing her capstone project for the film and media studies department about fan fiction. Another former participant in the "Fan Culture" class, Foster is focusing on "how slash fan fiction often elides the use of lubrication in anal sex" and how this omission by writers operates within a "heterosexual paradigm, a heterosexist use of queer characters in fiction written by women, for women."

She argues in her project that "fan writers explore femininity and build desirable forms of femininity through slash fanfiction by sticking feminine attributes on male characters and making them androgynous/feminine." She also proposes that "the lack of lubrication [...] and the primacy of anal sex [...] implies the anus as the vagina," which again privileges straight sexual relationships.

While fan fiction is still apparently a rarity even at Swarthmore, Ginzberg and Foster prove that the practice has its Swattie devotees, who treat writing fan fiction with both a sense of fun and of respect. Whether inside or outside the classroom, or in both spheres, these Swarthmore writers apply intellectual inquiry to this wildly popular creative practice.

Comments

Post a Comment