ART REVIEW: Speculative collages of Saba Taj at Twelve Gates Arts re-imagine the future through a queer, brown perspective

In post-apocalyptic Hollywood blockbusters like Elysium, the survival of the downtrodden human race is led by Matt Damon. In of beast / of virgin, Saba Taj’s current show at Twelve Gates Arts, the future is queer, and femme, and Indian, and Muslim, and from the global South — representing a true ascension of oppressed peoples into power. Taj aims to give us one potential outcome of the destruction of the earth: a flowering of new ways of living, of new possibilities that can only come from the most desolate and bleak of scenarios. What will this world become? What strange creations will emerge from the ashes of neglect and destruction?

Working in mixed-media collage on paper and canvas, Taj has not only created hypothetical portraits of potential inhabitants of Earth’s future habitats, but has structured the exhibition around several different themes, including the new natural world and the future of gender roles. Their surrealist collage compositions recall notable Afrofuturist artists like Wangechi Mutu and Manzel Bowman, or the more cosmic imagery of Pakistani artist Mehreen Murtaza.

As evidenced by several of the most intriguing works in of beast / of virgin, Taj envisions this brave new world as something beyond human. In their artist statement, Taj brings to mind the fiction of Octavia Butler, citing a process of “hybridization,” where the “boundaries between species, gender, bodies and environment [have] collapsed.” In practical terms, this biological process results in Taj using the collage medium to mix and match animal and human body parts together in imaginative and amusing ways. As you move from left to right within the gallery space, the whisperings of change emerge with a cluster of small drawings on paper placed by the artist statement. “Microbez,” “Gol gol gol,” “Networking,” and “Organizm” seem to depict a kind of mitosis, of cells growing and multiplying and dividing. In “body/gaze 1, 2, and 3” these tiny blobby spheres (that in some cases mimic the appearance of breasts) start to simulate and attach themselves to human bodies, slowly covering them.

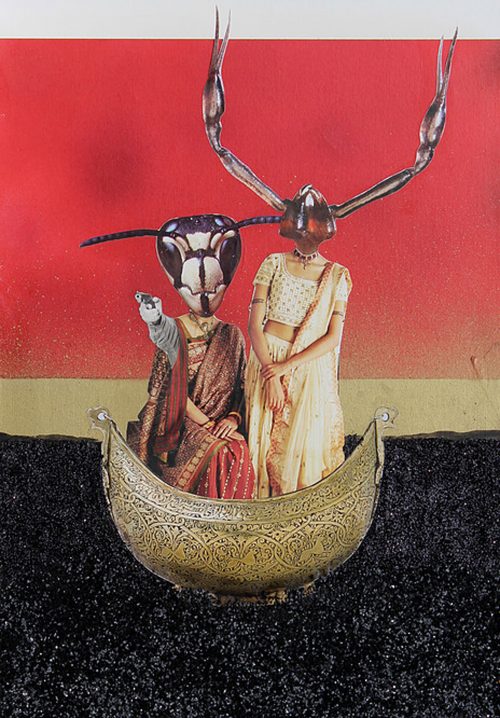

In works like “Engendered Species” and “Suck My Dowry,” the combination and mutation of living forms is more precise and expected: animal heads are grafted onto human bodies. But in “The Flood,” and “Blue,” we see that Taj aims to upend the entire biological systems of evolution and adaptation we have come to expect and understand on Earth. “The Flood,” for example, features a rooster’s head on a multi-armed human torso, but also has a cow’s head and another human head extending a sinuous snake’s tongue grafted on top of the rooster’s head, indicating that the new world in of beast / of virgin isn’t just a shuffling and reorganization of human and animal features, but is instead a total re-imagination of these different bodily components and what they might mean together. It’s a total re-conception of evolutionary adaptations and organs. In this new world, Taj argues, humanity and all organic life must come up with entirely new ways of living, discarding the usual biological templates. It is a complete upheaval of how we conceive of science and evolution, and of different biological and (as we see later) societal niches.

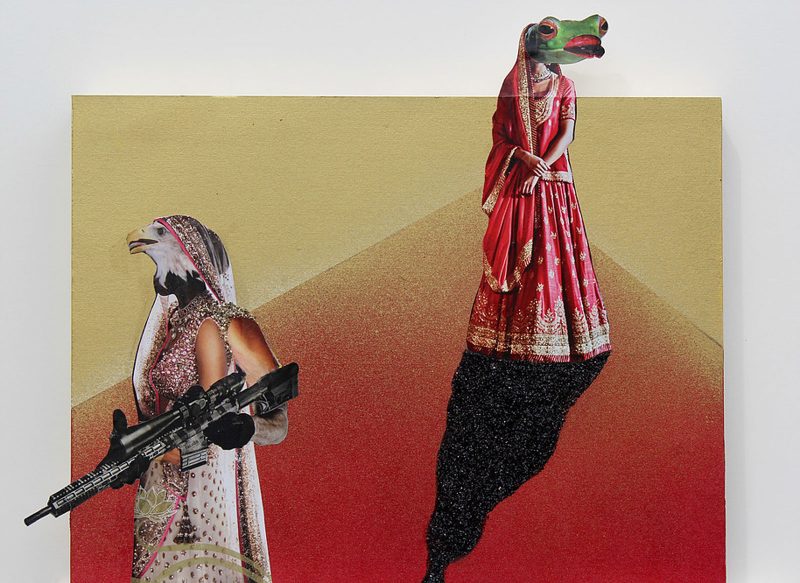

Taj further explores the social possibilities in a reborn world where the old rules governing behavior and violence don’t apply. A series of four small works on canvas (whose flat, spare backgrounds and stylized posed figures recall early Renaissance/late Byzantine art among others) portray the reaction of numerous human-animal hybrids to the emergence of a new civilization. Indeed, The Enunciation purposefully mimics a typical “annunciation” composition, where a kneeling figure delivers news to a taken-aback Virgin Mary. Here an elephant-headed figure clothed in a lavish sari seems to cry out, frightened; it’s hard not to see the ornate clothing of the figures in these four works as a reference to how the most fortunate and wealthy will react to impending threats. In “Engendered Species,” another sari-clad figure, this time with an eagle’s head and an assault rifle, seemingly watches out for its frog-headed companion. (The combination of the symbols of a bald eagle with an assault rifle unmistakably calls to the mind American imperialist urges.) The takeaway from this cycle is potentially bleak, suggesting a fear of reproducing the dynamics of exploitation and privilege that governed the old world.

In of beast / of virgin, Saba Taj artfully subverts (even sabotages, we could say) common conceptions of the end of the world as a descent into endless hellish suffering. Offering destruction as an opportunity for both an ecological rebirth and a possible re-imagining of very human power dynamics, Saba Taj creates a rich and vibrant new world.

Working in mixed-media collage on paper and canvas, Taj has not only created hypothetical portraits of potential inhabitants of Earth’s future habitats, but has structured the exhibition around several different themes, including the new natural world and the future of gender roles. Their surrealist collage compositions recall notable Afrofuturist artists like Wangechi Mutu and Manzel Bowman, or the more cosmic imagery of Pakistani artist Mehreen Murtaza.

As evidenced by several of the most intriguing works in of beast / of virgin, Taj envisions this brave new world as something beyond human. In their artist statement, Taj brings to mind the fiction of Octavia Butler, citing a process of “hybridization,” where the “boundaries between species, gender, bodies and environment [have] collapsed.” In practical terms, this biological process results in Taj using the collage medium to mix and match animal and human body parts together in imaginative and amusing ways. As you move from left to right within the gallery space, the whisperings of change emerge with a cluster of small drawings on paper placed by the artist statement. “Microbez,” “Gol gol gol,” “Networking,” and “Organizm” seem to depict a kind of mitosis, of cells growing and multiplying and dividing. In “body/gaze 1, 2, and 3” these tiny blobby spheres (that in some cases mimic the appearance of breasts) start to simulate and attach themselves to human bodies, slowly covering them.

|

| Suck My Dowry, 2016, 16.5” x 12”, Collage, spray paint, glitter on paper, mounted on panel. Image and description courtesy of the artist’s website. |

Taj further explores the social possibilities in a reborn world where the old rules governing behavior and violence don’t apply. A series of four small works on canvas (whose flat, spare backgrounds and stylized posed figures recall early Renaissance/late Byzantine art among others) portray the reaction of numerous human-animal hybrids to the emergence of a new civilization. Indeed, The Enunciation purposefully mimics a typical “annunciation” composition, where a kneeling figure delivers news to a taken-aback Virgin Mary. Here an elephant-headed figure clothed in a lavish sari seems to cry out, frightened; it’s hard not to see the ornate clothing of the figures in these four works as a reference to how the most fortunate and wealthy will react to impending threats. In “Engendered Species,” another sari-clad figure, this time with an eagle’s head and an assault rifle, seemingly watches out for its frog-headed companion. (The combination of the symbols of a bald eagle with an assault rifle unmistakably calls to the mind American imperialist urges.) The takeaway from this cycle is potentially bleak, suggesting a fear of reproducing the dynamics of exploitation and privilege that governed the old world.

|

| Engendered Species, 2016, 14” x 16”, Collage, spray paint, glitter, ink on paper, mounted on panel. Image and description courtesy of the artist’s website. |

Many of the figures in these compositions have three or four arms, recalling depictions of Hindu deities. Yet in these works, the arms bearing weapons are obviously artificial attachments rather than original limbs. The hands that hold the rifle in “Amrikan Gothic” are smaller than those belonging to the central figure and are slotted into its elbow creases. In “Suck My Dowry,” a beautifully-dressed, feminine figure points a gun at the viewer, escaping with a compatriot in a small boat on a sparkling black sea, indicating a possible escape from patriarchal obligations of marriage. Notably, where the rest of the figure is in color, the hand that shoots at us in “Suck My Dowry” is taken from a black-and-white photograph of a cowboy. It’s as if these extra, weapon-holding hands didn’t emerge organically from their bodies, but rather were chosen to do the dirty, violent work of self-defense and survival. It’s possible to read into this set of works both an allegory of the defensiveness of the powerful and a potential empowerment of the oppressed, embodied by these figures that have taken on compound gender characteristics to thrive.

In of beast / of virgin, Saba Taj artfully subverts (even sabotages, we could say) common conceptions of the end of the world as a descent into endless hellish suffering. Offering destruction as an opportunity for both an ecological rebirth and a possible re-imagining of very human power dynamics, Saba Taj creates a rich and vibrant new world.

Comments

Post a Comment