ART REVIEW: ‘ABOLITION NOW!’ at Asian Arts Initiative examines racism and mass incarceration in America

|

| Installation view, ABOLITION NOW! at Asian Arts Initiative. Photo by Jino Lee. |

While the exhibition features instances of Asian American incarceration in the United States, the overall goal is to present a larger pattern of incarceration that implicates white supremacy in the United States, and how that philosophy manifests in the oppression of people of color. Milestones and hallmarks of American incarceration are presented in red text on the white walls, creating themed sections of the exhibition that tackle: the institution of African-American slavery; the 1940s Japanese-American internments; the prison management system and its transition from government ownership to private prisons run by multi-national corporations (dubbed the prison industrial complex); to the current concentration camp conditions for Central American refugees and immigrants dotting the Mexican border. ABOLITION NOW!’s strength as an artistic and political statement lies in how the artists and activists themselves make connections between these historical modes of incarceration and contemporary practices.

“Oil, Bananas, Prisons,” a collaborative work by Sara Zia Ebrahimi and Gralin Hughes, combines video projection with textiles to tell the story of how American imperialism has affected not just the Muslims who are banned from coming here now or the Central American refugees being held at our border, but how those two groups are linked irrevocably by American imperialism. Specifically, the label text mentions the 1953 coup of Iran’s elected leader Mohammad Mossadegh, and the 1954 coup in Guatemala to benefit the United Fruit Company’s “banana republic,”, Both coups were the work of the CIA to protect what it saw as American interests in oil (Iran) and bananas (Central America). The prisons of the work’s title make up the third leg of this relationship, as private prisons crop up across America, to hold and control the flow of refugees fleeing from countries like Guatemala that remain unstable largely as a result of American interference. As presented by Ebrahimi and Hughes, the cycle is unceasing, refusing to let us treat these incidences as isolated.

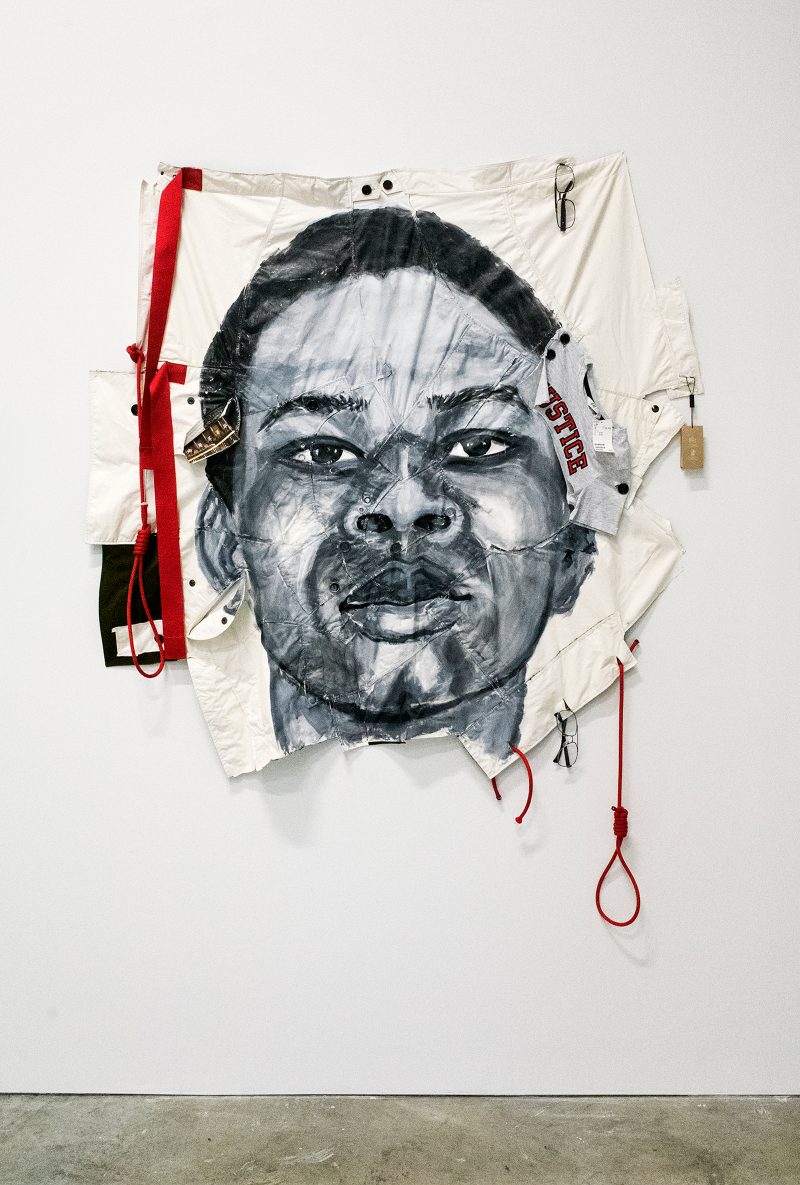

The gray-scale portrait of Michael Donald (a victim of lynching in 1981), titled “Mockery” and painted onto a fashionable tan jumpsuit, that references Burberry’s infamous hoodie with a noose makes an immediate, direct impression as it condemns tendencies of appropriating and decontextualizing props and hallmarks of oppression. Russell Craig, a returning citizen and self-taught artist and their mixed media “Mockery” links together lynching, the prison complex and high end fashion as institutions that endanger Black bodies.**

|

| Russell Craig, “Mockery,” from ABOLITION NOW! at Asian Arts Initiative. Photo by Jino Lee. |

“As a blk womyn, / It’s not like I didn’t know / America kills / United States death / Taxes paid with blood and breath / Auction block goodbyes / And then I learned more / Dug deep into hidden truths.”

It’s as if Badhey’s photograph of that spongy mushroom peeking out of the tree trunk and emerging from it is in sync with Robinson’s choice to learn, to grasp for new knowledge and understanding.

In another diptych in “Land Witness,” a photograph depicting a tall, thin monument capped with an eagle is shot from a low angle, partially blocking out the sun. The accompanying lines of poetry begin “They do what they want / ‘Papers’ don’t mean anything” and end with “Marked, then rounded up / One hundred, twenty thousand / Citizens of this / Great and noble land / Kept captive without a sound / Government decree.” The eagle, the emblem of the United States, sits at the top of the monument, towering above the viewer, which visually emphasizes the actions of the United States government described in the poem as something fearsome and cruel. The words and the images reinforce one another, and the message.

The second half of ABOLITION NOW! transitions from the global and historical to the local and contemporary. One set of paintings is a project of the Youth Art & Self-Empowerment Project, which works to stop the practice of trying young people as adults in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The works, created in concert with incarcerated youth, feature images of globes and hands with broken chains, envisioning a world without prisons. Just around the corner, the fashion hoodie-noose cited by Craig is a reminder that the hallmarks of punishment and incarceration are viewed as aesthetics instead of as tools of oppression to be obliterated. Also on display are striking posters created by the People’s Paper Co-op, a local project that advocates for incarcerated people. These posters, produced in collaboration with artists such as Molly Crabapple, raised money for the Philadelphia Community Bail Fund, helping incarcerated women who didn’t have the money for cash bail. The underlying message of these two projects is about the urgency of collaboration, of solidarity, of skill-sharing, and of mutual aid in the struggle for justice.

|

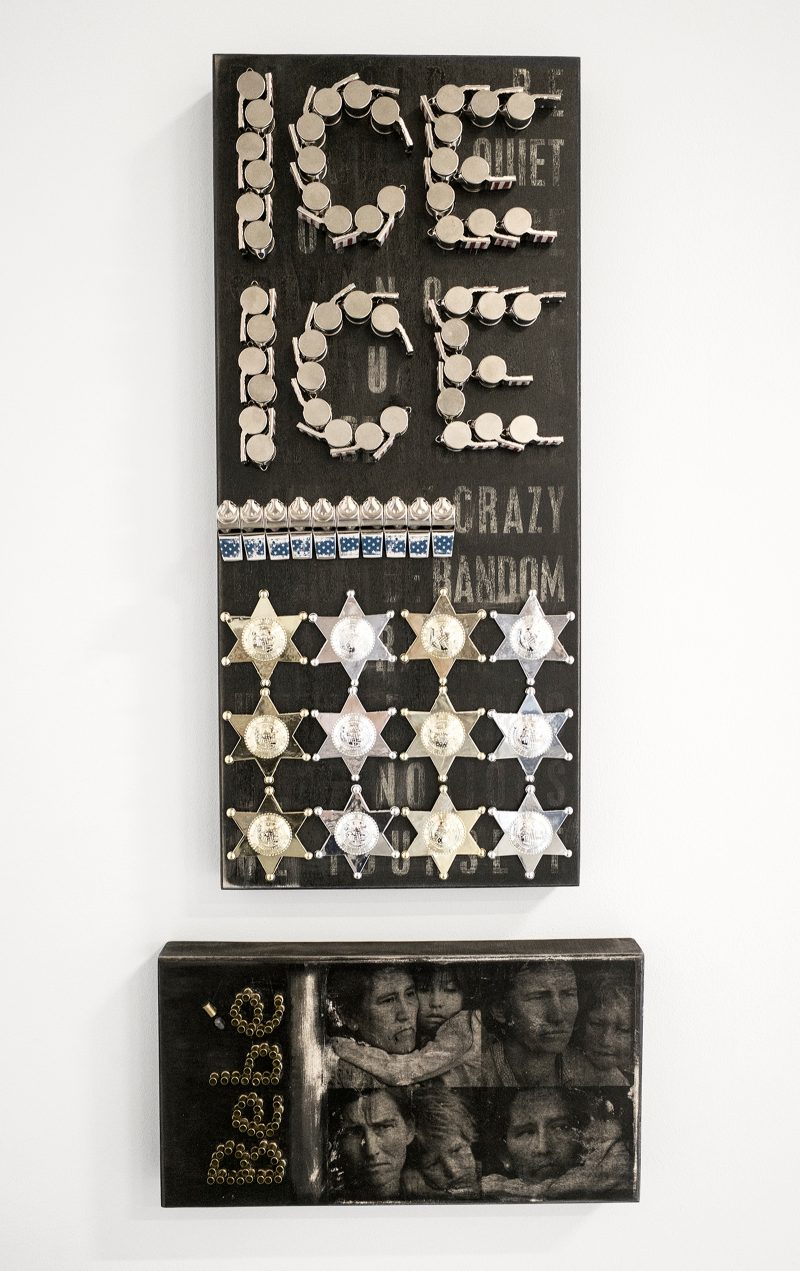

| From ABOLITION NOW! at Asian Arts Initiative. Photo by Jino Lee. |

**Similarly, the upcoming HBO television show Confederate, telling an alternate history of the American South in which the Confederacy won, and slavery is still legal in the 21st century, is another instance where the motifs and symbols of oppression, become nothing more than frivolous art or entertainment.

Comments

Post a Comment