ART REVIEW: Larissa Fassler’s cartography at the Currier Museum describes socioeconomic disparities in Manchester

For me, the best way to experience a city is on foot--slipping through historic cobblestone alleyways; darting across one-way streets and making apologetic eye contact with an errant driver; observing the shifts from older architectural forms to more contemporary ones; watching what Jane Jacobs called "the ballet of the good city sidewalk"-- the ebb and flow of people in their daily living habits. That tenet has led me to walk for miles through the streets of Philadelphia, Los Angeles (where possible), New York, Boston, Providence, Vienna, Prague, Zagreb, Venice, and Amsterdam until my feet are rendered into blistered, aching blobs squeezed into Doc Martens.

Clearly, Larissa Fassler would agree: her practice of critical cartography is dedicated to bringing the layered elements of urban life together in one visible sweep. In Critical Cartography: Larissa Fassler in Manchester, currently on view at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, NH, Canadian-born, Berlin-based artist Fassler trains her rigorous lens on the largest city in the Granite State.

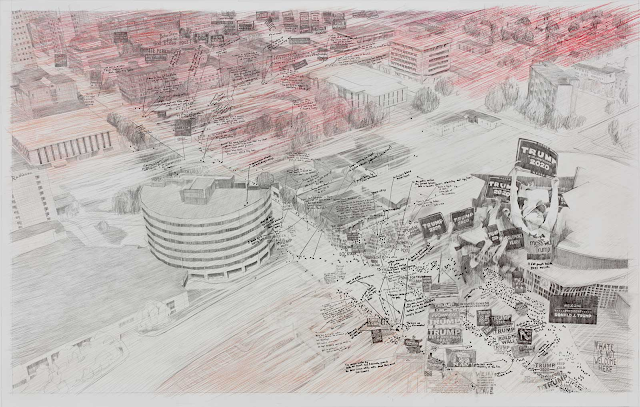

The discipline of critical cartography can be described as "linking geographic knowledge with power"; essentially, it involves the creation of maps that don't pretend to be neutral documents, but rather reveal how place influences and embodies existing social relations. The product of Fassler's 2019 participation in the Currier's Artists in the Community social practice artist residency, Critical Cartography translates academic and theoretical practices in a way that is meaningful and resonant for Mancunians (the demonym for the residents of Manchester). During her residency, Fassler walked around various neighborhoods in downtown Manchester, playing the role of flaneur as well as occasionally interacting with the world around her. The artist layers statistics and observational anecdotes atop meticulous, detailed aerial drawings using the format of a classic two-dimensional Nolli map and populated with data from online mapping tools. Fassler's critical mapping envisions the city as a palimpsest--a compendium of buildings and streets plus information and details of spaces and encounters over time.

The largest drawing of the four drawings, "Manchester I," functions as a thesis statement for her project, combining motifs and pictorial elements that will recur to varying degrees in the other drawings. An aerial view of part of downtown Manchester is the backdrop for the stunning inequities hidden by the city's architectural charm and endless parking lots. The practice of critical cartography is meant to bring what a map does not traditionally show to light. Newspaper headlines, bar graphs, pull quotes, and statistical tables discussing poverty, the opioid crisis, the lack of affordable housing, and other contemporary issues in Manchester (and New Hampshire as a whole) are rendered in neat handwriting in dark pencil. A sampling of the snippets reveals the following: "40% of Manchester's households have excessive housing costs"; "in NH, 88% of homicides in 2015 were domestic violence related"; "Close to 15,000 Manchester residents are without health insurance (2009-2011)"; "Senate passes bill to raise New Hampshire's minimum wage;" "[Governor] Sununu, citing 'booming' state economy, vetoes bill to hike hourly minimum wage to $10-12."

Fassler has developed her own key to interpreting another dimension of her maps: red hatched lines are meant to reflect crime reports in a given specific area, while the erasure of various groups of people is literally depicted through erase and smudge marks. Many locations are labeled, with a particular focus on spaces that are meant to serve the public: the Manchester City Library, the YWCA, the First Congregational church. Drawings of "privacy" and "no trespassing signs" and in the upper left corner, a cluster of Trump signs and slogans hints at a hostility simmering beneath the surfaces of the drawings.

Yellowish bubbles with rent costs, many in the 1-2 thousand dollar range, hover above many of the buildings. And lastly, with thin strokes clinging to the surface of the drawing like spiderwebs, the artist has written her own observations of the city--and her occasional encounters with its people--in the precise places where they occurred, each marked with an "x."

Studying Fassler's anecdotal texts closely, it becomes evident how she chose, in some circumstances, where to layer location, statistics, and stories. Rendered only in the lightest of pencil strokes, Victory Park (bounded by YWCA at the top and the Manchester City Library at the bottom) serves as a hub for the city's unhoused populations; consequently, the most damning informational elements related to homelessness are depicted just below, almost swallowing the library whole. Fassler also notes the casual cruelty of anti-homeless laws, making the availability of the park all the more necessary: "Although there are 2 benches in front of the library, there is also a sign that says no loitering!--confusing."

Limiting itself to a few blocks in the downtown core, "Manchester II" focuses on a section of "Manchester I," with many of the anecdotes and their locations repeated for clarity and continuity. Yet instead of repeating the statistics of "Manchester I," "Manchester II's" uses an underlying backdrop of menu items from local restaurants to highlight the divide between who is welcome and who is not. An offering of "Spinach and Artichoke Dip" for $10.99 is adjacent to where Fassler has recorded this encounter: "Man and woman sit on planter / Man asks me if I can spare any change / Normally I say No. But I am tired of saying no so I give him 2 dollars hoping he will share with the woman / 'Thanks!' he says / 'Have a good day.' 'You too' I say."

Comments

Post a Comment